Screenplay Structure: Tips to Engage Audiences

There are two schools of thought regarding screenplay structure: those who believe it must be adhered to without fail and those who think it’s overrated. The truth is somewhere in the middle. You do need a structure for your story; without it, you won’t have a story. However, structure doesn’t have to be rigid and limit creativity. Today, I’ll cover how to walk this line and break down everything you need to know about screenplay structure.

Below, you’ll learn:

- The ideas and concepts behind plot construction

- How the typical 3-act structure works

- Several alternative story structures and their pros & cons

- The structure I recommend writers use and why

- Some advice and tips on structure

- The answers to some frequently asked questions

From the basics of story structure and why it’s important, different options you can use, and when you should break the rules, I’ve got you covered. Below, we’ll cover everything mentioned above in great detail, look at real-world examples, and touch on what your screenplay needs beyond structure. Ready to learn? Good. Let’s get started.

Learning Screenplay Structure

At its most basic level, when we say structure, we’re talking about a beginning, middle, and end for a story. Slightly below the surface are concepts of pace and what happens during the beginning, middle, and end.

Having a good grasp on the structure of your story ensures that you have a cohesive, well-paced story that your audience can follow, making your job as a writer much smoother.

With that very basic definition out of the way, let’s look at some commonly used screenplay structures, how they work, and their pros and cons compared to what many consider the standard approach.

Screenplay Narrative Frameworks

Screenplay narrative frameworks are templates that screenwriters use to organize the narrative elements of their scripts effectively. These frameworks guide the story’s progression, including plot points, character development, and thematic elements.

In short, they help us maintain coherence and ensure that the screenplay engages the audience from beginning to end. Examples of screenplay narrative frameworks include the three-act structure, the hero’s journey, the sequence approach, and Dan Harmon’s story circle amongst many more.

Each one offers a unique approach to storytelling, allowing writers to experiment with different narrative techniques and find the structure that best suits their story’s needs. By understanding and utilizing these frameworks, you can create narratives that resonate with audiences and increase their chances of being accepted for production.

Let’s break down a few of the most common structures, along with their pros and cons.

The 3-Act Structure

When discussing screenplay structure (or any storytelling), few frameworks hold as much sway as the Three-Act Structure. Like a well-trodden path, it offers writers a roadmap to guide their characters from tranquility to exposition through some conflict and, finally, to a resolution.

Overall, it is a simple and relatively effective way to structure your work. However, it doesn’t offer writers much in terms of plot direction, and many people struggle to write their plots within this framework, especially in Act Two.

Here’s a rundown of a typical 3-act film structure:

Act 1: Setup

Act one is the beginning of the story, where we introduce characters, setting, and central conflict. It also “incites incidents” and triggers events that disrupt the protagonist’s ordinary world and set the story in motion. This first act usually makes up around 25% of the overall screenplay.

So, this first act will be about 30 minutes long in an average-length film.

Act 2: Confrontation

As we move into Act Two, the conflict we set the stage for in Act One will begin to rise in tension. The protagonist reacts to the inciting incident, faces initial obstacles, and begins pursuing their goal. Then comes a turning point where the protagonist’s journey takes a significant turn, often involving a revelation or major confrontation.

This act is around 50% of the screenplay or, on average, about an hour of screen time.

Act 3: Resolution

As you move into the final act, the tension should increase even more – The stakes are raised as the protagonist encounters more significant challenges and obstacles. This builds up to a crisis or climactic moment where the protagonist faces their greatest obstacle or conflict, leading to a moment of decision or revelation.

This leads directly into the story climax, showdown, or confrontation, where the protagonist confronts the antagonist and resolves the central conflict. Finally, the resolution or aftermath of the climax, where loose ends are tied up, is where the story reaches its conclusion.

Like Act I, this final act is usually around 25% of the total screenplay.

| Pros | Cons |

| Provides a solid foundation for structuring the screenplay | Requires careful pacing and timing to ensure that plot points are effectively executed |

| Focuses on key plot points that drive character development and conflict. | May feel restrictive to writers who prefer more organic or nonlinear storytelling. |

Hero’s Journey

The Hero’s Journey, follows a protagonist through various stages of growth and transformation as they embark on an adventure, face trials, and ultimately return home changed. The plot points are usually as follows:

- The Ordinary World: Introduces the hero in their everyday life, often showing their routines, relationships, and challenges before the adventure begins.

- The Call to Adventure: The hero receives a call to action, prompting them to leave their ordinary world and embark on a journey or quest.

- Refusal of the Call: Initially, the hero may resist the call to adventure due to fear, doubt, or reluctance to leave their comfort zone.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a mentor figure who provides guidance, wisdom, or tools to help them on their journey.

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero commits to the adventure and crosses into the unknown or unfamiliar world, leaving behind their ordinary life.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero faces various trials, encounters allies who assist them, and confronts adversaries who challenge their progress.

- Approaching the Inmost Cave: The hero approaches a significant challenge or ordeal, often represented as a metaphorical “cave” where they must confront their deepest fears or obstacles.

- The Ordeal: The hero undergoes a major test, battle, or transformation, symbolizing their growth and development as they overcome adversity.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword): After overcoming the ordeal, the hero receives a reward, insight, or new knowledge that empowers them to continue their journey.

- The Road Back: The hero begins the journey back to their ordinary world, facing new challenges or obstacles along the way.

- Resurrection: The hero faces a final, climactic challenge that tests their newfound abilities and resolves any remaining conflicts.

- Return with the Elixir: The hero returns to their ordinary world, bringing back the lessons, treasures, or gifts gained from their journey, which may benefit themselves or their community.

| Pros | Cons |

| Provides a rich framework for character development and thematic exploration. | Can sometimes feel formulaic or predictable if not executed with originality. |

| Familiar for audiences, leading to greater engagement and emotional connection. | May require additional narrative elements to flesh out the story beyond the basic hero’s journey structure. |

Save the Cat! Beat Sheet

Developed by Blake Snyder, the Save the Cat! Beat Sheet outlines specific “beats” or story moments that should occur at particular points in the screenplay, such as the opening image, catalyst, midpoint, and finale. However, it has built-in mechanisms for a subplot that runs alongside the main story, which is helpful for adding depth and emotional resonance.

Here are the key beats of the Save the Cat! Beat Sheet:

- Opening Image: Sets the tone and introduces the audience to the story’s world. It often contrasts with the closing image to show the protagonist’s journey.

- Theme Stated: Establishes the central theme or message of the story, often through dialogue or characters’ actions.

- Set-Up: Introduces the protagonist, their ordinary world, and any key relationships or conflicts. It lays the groundwork for the story to come.

- Catalyst: Also known as the “Inciting Incident,” this event disrupts the protagonist’s ordinary life and sets them on the path of the main story.

- Debate: The protagonist reacts to the catalyst and decides to embark on the journey or stay in their comfort zone. This is often an internal struggle.

- Break into Two: The protagonist makes a clear decision to pursue the goal or accept the challenge presented by the catalyst, officially beginning the journey.

- B Story: Introduces a secondary storyline or relationship that runs parallel to the main plot. It often provides emotional depth or thematic resonance.

- Fun and Games: The protagonist explores the new world of the story, encountering obstacles, allies, and adversaries. This section is often marked by humor, action, or excitement.

- Midpoint: A significant turning point in the story where the protagonist faces a major obstacle, revelation, or reversal of fortune. It raises the stakes and shifts the direction of the plot.

- Bad Guys Close In: The antagonist or opposing forces become more threatening and the protagonist’s journey becomes more difficult. It builds tension and ramps up the conflict.

- All Is Lost: The lowest point for the protagonist, where they experience a major setback or defeat. It forces them to confront their flaws, doubts, or failures.

- Dark Night of the Soul: The protagonist grapples with despair, doubt, or inner conflict as they face the consequences of their actions. It sets the stage for their ultimate transformation.

- Break into Three: The protagonist finds renewed determination or discovers a new approach to overcome the final challenge. They commit to the final confrontation or resolution.

- Finale: The story’s climax, where the protagonist faces the main conflict head-on and succeeds or fails in achieving their goal.

- Final Image: The closing image of the story reflects the protagonist’s growth, transformation, or the outcome of their journey. It often echoes the opening image to provide narrative symmetry.

| Pros | Cons |

| Provides a clear roadmap for structuring the story and ensures key story beats are hit at the right moments. | Can feel formulaic if followed too closely without room for creativity. |

| Emphasizes the importance of audience engagement and emotional resonance. | May not suit every story or genre, as some narratives may benefit from a more unconventional structure. |

| Easily incorporates subplots. |

Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

Dan Harmon’s Story Circle is a framework based on Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, (also known as the Hero’s Journey), which we covered above. The Story Circle is a simplified version that breaks storytelling into eight key stages, each representing a different phase of the protagonist’s journey.

Harmond developed his Story Circle after observing that all stories (regardless of style, genre, or medium) seemed to follow a basic cadence.

According to Dan, the reason is that the non-linear pattern occurs throughout our lives daily—life and death, conscious and unconscious, chaos and order, etc. To quote the man himself, “Our society, each human mind within it, and all of life itself has a rhythm, and when you play in that rhythm, [your story] resonates.”

While that may sound a bit corny, in my experience, it’s true. Very few things in life are as linear as we make them in a story. This ever-present circular aspect allows the story circle to be applied to entire manuscripts, single acts, characters, scenes, conversations, etc.

Here’s an explanation of each stage and how it differs from traditional screenplay structures:

- You: Introduces the protagonist in their ordinary world, establishing their identity, desires, and flaws. This stage is similar to the Setup or Ordinary World in other structures, where the audience gets to know the main character before the adventure begins.

- Need: The protagonist encounters a problem or desire that sets them on a path of change. This stage is akin to the Catalyst or Inciting Incident, where something disrupts the protagonist’s ordinary life and prompts them to take action.

- Go: The protagonist commits to pursuing their goal and embarks on the journey. This stage aligns with the Break into Two or Crossing the Threshold moment, where the protagonist decides to pursue their objective.

- Search: The protagonist faces obstacles, learns lessons, and gains allies as they navigate the new world of the story. This stage corresponds to the Fun and Games or Tests, Allies, Enemies phase, where the protagonist encounters undergoes character development.

- Find: The protagonist achieves their initial goal or discovers what they were searching for, but it comes with a price or unexpected consequences. This stage is similar to the Midpoint or False Victory, where the protagonist experiences a significant revelation or turning point.

- Take: The protagonist must deal with the aftermath of their actions and face the consequences of their choices. This stage mirrors the Bad Guys Close In, or All Is Lost moment, where the protagonist confronts setbacks that test their resolve.

- Return: The protagonist returns to their ordinary world, changed by their experiences and ready to apply what they’ve learned. This stage corresponds to the Break into Three or Resurrection phase, where the protagonist prepares for the final confrontation or resolution.

- Change: The protagonist undergoes a final transformation or revelation, completing their character arc and bringing closure to the story. This stage aligns with the Finale or New Status Quo, where the protagonist achieves their goal and experiences personal growth.

| Pros | Cons |

| Offers a simplified yet effective framework for structuring the story and exploring character arcs. | Doesn’t provide as rigid of a structure as some other systems |

| Emphasizes the cyclical nature of storytelling and the importance of transformation | May require adaptation to fit the needs of each story |

| Can be adapted to fit almost any story | |

| Can be applied to characters, scenes, & acts |

LivingWriter Structure Templates

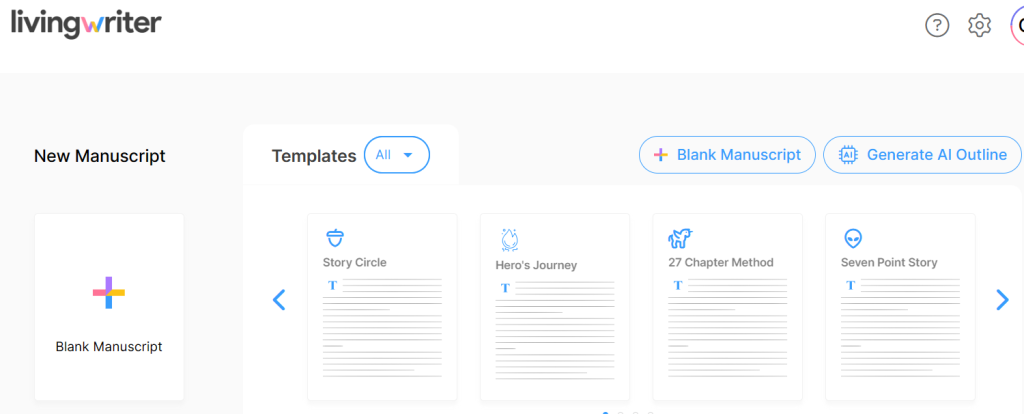

LivingWriter allows you to use each structure mentioned above (and many more) as a template.

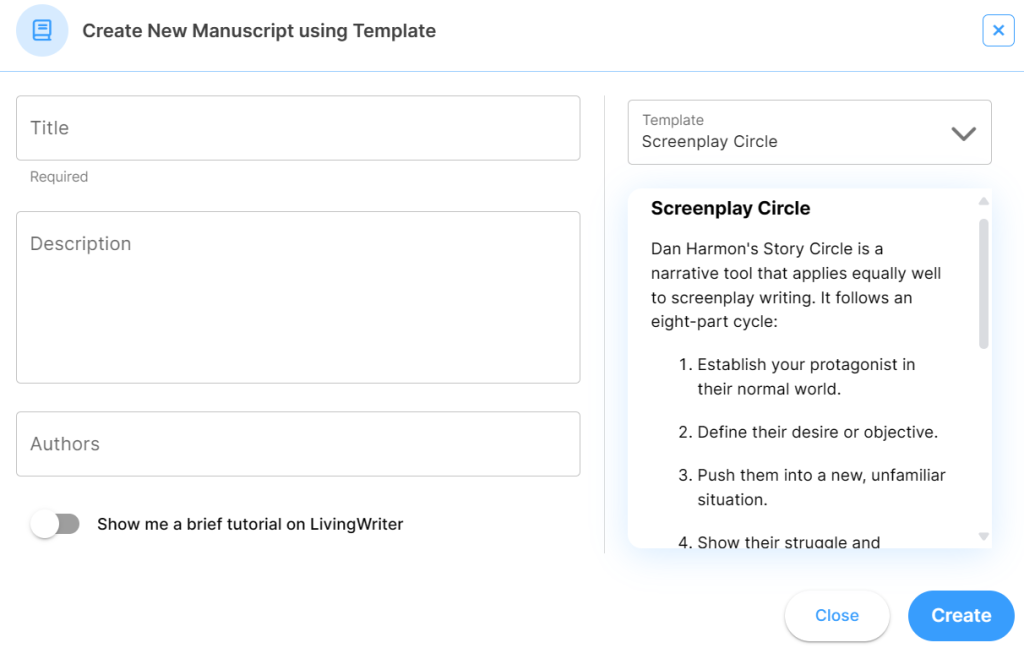

Start a new manuscript, select which template you want, and fill in some basic info. At this point, you’ll also be given a basic rundown of the structure you choose:

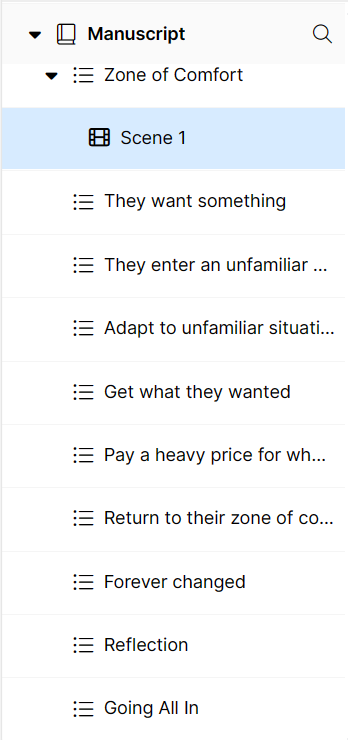

Once you’ve created the manuscript, all of the major points are pulled directly into the manuscript to have a visual aspect of the structure as you write. Click on a specific part to add chapters, scenes, dialogue, etc for that section.

Having everything mapped out and applied to your manuscript makes it much easier to know you’re on the right track for the story structure you’ve selected for your screenplay.

Which Story Structure Should You Use?

So, we’ve covered screenplay structures and a few of the most common ones. While that’s a good first step, it doesn’t help determine which is best or which you should use. After all, different videos, articles, books, and people all say different things.

As for my two cents, I recommend a Three-Act Structure with Dan Harmond’s Story Circle. I’ll tell you why: A three-act structure covers your bases in the simplest way possible. Meanwhile, the Story Circle offers some guidance for structuring smaller portions of the story that could be problematic.

Let me elaborate.

Big & Small Picture

The formulaic style of the Three-Act Structure provides an excellent overall framework without being overly specific about beats or plot points. The Story Circle makes up for what it lacks in specific direction by applying to non-linear scripts, individual acts, characters, scenes, or any other problematic section.

This one-two punch also works for almost any genre or story type.

Just like a chef doesn’t just focus on the overall recipe but also on the quality of each ingredient, the three-act structure and story circle allow writers to zoom in and meticulously sculpt every aspect of their narrative when needed. It’s akin to having a Swiss Army knife for storytelling, offering precision and versatility at every turn. You have a blueprint for your manuscript and the individual sections that make it up.

You May Also Like: Writing Compelling Screenplays – 6 Advanced Tips

For a very detailed breakdown of how the story circle at work in every aspect of the Silence of the Lambs (which came out way before Harmond coined this structure), check out this great YouTube video:

Practical Tips & Advice For Screenplay Structure

You should now have an idea of screenplay structure, why it’s important, some of the common structures, and my overall top pick. Now, let’s dive into some actionable tips you can use regarding structure to make your writing better and more engaging.

1. Master the Three-Act Structure

As mentioned, the three-act structure is somewhat of an industry standard. While it isn’t exciting (or perfect), you’d do well to understand the fundamentals it provides—the typical beginning, middle, and end, establishment of characters and setting, rising action and conflict, and resolution.

You may be surprised at how engrained this structure is in major motion pictures. You can try it yourself: Take the overall length of a movie and quarter it, then set a timer. You’ll find that the first act will end at that 25% mark when the timer goes off.

If you time the second act, you’ll find it to be almost exactly double the first act. Finally, the final act will match the first in length. In my experience, this is true nine times out of 10. It’s ever-present because it works, and even if it’s unconscious, audiences are familiar with and accustomed to this pace.

2. Introduce Intriguing Premises

I’ve discussed this in other articles. Naturally, your first act sets up more exciting things to come. However, you don’t have time to waste before getting excited about the story. Using Act One only as a set up the rest of the story and having a very slow-burning pace isn’t going to cut it.

Start your screenplay with a premise or situation that immediately captures the audience’s attention and makes them eager to learn more.

3. Craft Dynamic Character Arcs

Your narrative needs a beginning, middle, and end, and so do your characters. They should change as the plot moves forward. If your Act One character is exactly the same as your Act Three character, you likey don’t have enough evolution happening.

You May Also Like: How To Write Unique Characters With LivingWriter

Developing living, multi-dimensional characters with clear goals, obstacles, and growth arcs throughout the story contributes to the narrative and keeps viewers invested in their fates.

4. Create Tension And Conflict

Tension and conflict are what will keep viewers watching and potential buyers turning pages. While some of the stress and conflict are related to the plot itself, a lot is lost or gained in the structure and presentation. For example, balancing conflict with moments of respite to create an ebb and flow, using foreshadowing, and gradually escalating conflict are all great tools.

Here is a list of ideas I want you to keep in mind regarding conflict and tension:

- Establish Clear Goals and Obstacles

- Increase Stakes and Risks

- Utilize Time Pressure

- Embrace Moral Dilemmas

- Incorporate Internal Conflicts

- Use Miscommunication and Secrets

- Employ Foreshadowing

- Escalate Conflict Gradually

- Create Empathy for Characters

- Balance Conflict with Moments of Respite

5. Utilize Pacing Techniques

Pace is the film’s flow (and speed) as perceived by the viewer. Have you ever watched a movie that seemed much longer than it actually was? It was probably poorly paced on the slow side. If a story is too fast-paced, it may feel rushed and unsatisfying.

Fast-paced films will have more scenes, but they’ll be shorter. On the other hand, a slower-paced film will have fewer overall scenes but they’ll be longer, which keeps viewers in a particular part of the story for longer. It’s important to mention that the pace has nothing to do with length. You can have a shorter, slow-paced film and vice versa.

While the final scene length often falls on the editor, it’s important to have an idea of your script’s pace. Then, you can use pacing techniques such as tempo and pacing variations to control the flow of your screenplay. You can also balance slower, reflective moments with high-energy action sequences to keep viewers engaged throughout.

6. Test and Iterate

Seek feedback from trusted peers, mentors, or script consultants to identify areas for improvement in your screenplay’s structure and pacing. Be willing to revise and refine your script based on constructive criticism to maximize its potential.

It’s also crucial how you ask for feedback. Instead of asking for general feedback (which tends to yield quite generic responses), ask specifically for one thing the person did or didn’t like. This way, you get something tangible you can use instead of a thumbs up or thumbs down that isn’t particularly productive.

7. Study Successful Screenplays

Analyze screenplays of acclaimed films known for their captivating storytelling to learn from established masters. Study how they structure their narratives, develop characters, and build tension to create compelling cinematic experiences.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here, I’ll answer some of the questions that seem to come up most often regarding screenplay structure.

Why is screenplay structure important?

Screenplay structure is crucial because it provides a framework for storytelling, helping writers effectively convey their ideas to the audience. It ensures clarity, coherence, and engagement, making the screenplay more compelling and easier to follow.

What are the key components of screenplay structure?

The key components of screenplay structure include acts, sequences, scenes, and beats. Acts divide the screenplay into major sections, while sequences and scenes further break the story into smaller units. Beats represent significant moments or turning points within scenes.

How do you create tension and conflict in screenplay structure?

Tension and conflict are essential elements of screenplay structure and can be created through various techniques, such as establishing clear goals for characters, introducing obstacles and challenges, and escalating stakes as the story progresses.

What role does pacing play in screenplay structure?

Pacing refers to the rhythm and tempo of the screenplay, which significantly influences the audience’s engagement and perception of time. By controlling pacing, writers can effectively build tension, maintain momentum, and keep the audience invested in the story.

How can I ensure my screenplay structure is effective?

To ensure your screenplay structure is effective, focus on developing well-defined characters, establishing clear goals and conflicts, maintaining a compelling narrative arc, and refining pacing to keep the audience engaged from beginning to end.

Receiving legitimate feedback on your work is also a great way to tell what’s working and what isn’t.

Are there different screenplay structures for different genres?

Yes and no. While the basic principles of screenplay structure apply to all genres, certain genres may have specific conventions or expectations regarding pacing, plot twists, and character development. For example, horror films often prioritize tension-building scenes that escalate suspense and fear.

Writers should tailor their approach to suit the genre requirements they are working in.

Can I deviate from the traditional screenplay structure?

While traditional screenplay structures provide a useful framework, there is room for experimentation and innovation in storytelling. Writers can deviate from conventional structures to create unique narratives, as long as they maintain clarity, coherence, and engagement for the audience.

How can I improve my understanding of screenplay structure?

Improving your understanding of screenplay structure involves studying scripts, analyzing films, and learning from experienced writers. Additionally, practicing writing screenplays and seeking feedback can help refine your skills and develop a deeper understanding of effective storytelling techniques.

What resources are available to help me learn more about screenplay structure?

There are numerous resources available to help aspiring screenwriters learn about screenplay structure, including books, online courses, workshops, and screenplay analysis tools. Writers can also benefit from joining writing groups or seeking mentorship from experienced professionals in the industry.

LivingWriter screenplay templates can help frame your work in the structure of your choosing and expand your working knowledge of them as you write.