Mastering Pacing In Novels And Screenplays

Pacing is the heartbeat of storytelling, dictating the rhythm and flow of your narrative, and it can be hard to do well. Whether you’re writing a novel or a screenplay, understanding pacing is essential for keeping readers and viewers engaged from beginning to end. This guide will explore fundamental techniques for controlling pacing and creating a dynamic reading or viewing experience.

Below, we’ll examine pace and its importance. Then, we’ll discuss some common mistakes and give advice on how to improve your pacing. I’ll discuss pacing tips for novels and screenplays, so regardless of your medium, I’ve got you covered. Without further ado, let’s explore everything you need to know about pacing in writing.

How To Pace A Screenplay Or Novel

As mentioned, we’ll be covering all aspects of pacing for both novels and screenplays. While the overall concepts are the same for both mediums, some things differ. For example, a novelist uses chapters to affect the pace, and a screenwriter uses acts, which changes a few things. With that said, let’s start with a general definition of pace in storytelling.

What Is Pacing In Writing?

Essentially, pace is the flow of the story, or how fast or slow the narrative moves along. While it has nothing to do with overall length (you can have a long, fast-paced film, for example), it contributes to the audience’s perception of time. Fast-paced things tend to feel shorter, and a slower pace can feel longer.

Think of pace as the number of scenes and the amount of time spent on each one. A slower-paced work will often have fewer scenes but they’ll be longer, keeping the audience engaged with each event for a more extended period. On the other hand, a fast-paced story will have more scenes but they’ll be shorter ones, showing more things for less time.

Most Common Pacing Issues

The idea of pace in storytelling is relatively straightforward, but it’s by no means easy to do well without practice. In my experience, a few common issues get writers into trouble with their pace. If you have trouble with it, these would be a perfect place to start looking. They are:

- Lack of Planning

- Fear of Cutting Content

- Misjudging Momentum

- Lack of subplots

Let’s break each one down.

Lack Of Planning

Let’s start with the lack of planning. Not everyone likes to map out their stories and stick to an outline. While you can write a great story without using a traditional structure, it helps a lot with the pace. Neglecting to have a clear plan for the story can lead to meandering plots or scenes that lack purpose or direction, which will hurt the flow of the story.

Fear Of Cutting Content

This leads me right to the next common issue: not wanting to cut unneeded content. Even with a plot, we will write things that aren’t strictly needed for the story. The less of this fluff we have in the finished product, the better it will be. On the other hand, too many scenes that don’t contribute to the conflict or plot meaningfully will kill momentum and cause the audience to lose interest.

As Stephen King once said, “Kill your darlings, kill your darlings, even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings.” This invaluable advice underscores the importance of cutting ruthlessly—even if it means letting go of cherished passages or characters. It isn’t easy to do, but your story and audience will thank you. When you find something that needs to go, let it go.

Misjudging Momentum

This one takes on many faces. Misjudging momentum occurs when a writer fails to accurately gauge the pacing needs of their story, leading to inconsistencies or imbalances in the narrative flow. Here’s how it might manifest:

- Rushed or Forced Scenes: Feeling pressure to move the story along quickly can result in rushed or underdeveloped scenes. This can happen when we try to fit too much plot progression into a single scene without allowing for proper buildup or character development.

- Slow or Ponderous Sections: Conversely, it’s possible to linger too long on certain scenes or storylines, resulting in sections that feel too slow. This can happen when writers become overly enamored with their own writing or fail to recognize when a scene has served its purpose and should be trimmed down or omitted.

- Inconsistent Pacing Within Scenes: A struggle to maintain a consistent pace within individual scenes leads to tension or energy level fluctuations. This can make it difficult for readers or viewers to fully immerse in the story, as they may feel jerked around emotionally from one moment to the next.

- Failure to Build Anticipation: Misjudging momentum can also result in a lack of anticipation or suspense, as we may neglect to foreshadow future events or properly build tension throughout the story. Without these elements, readers or viewers may not feel compelled to finish the story.

Lack of Sub-Plots

A solid main plot is essential. But even a well-executed “A Plot” isn’t enough to carry the entire story. It often results in a thin, rushed storyline or the need to pad the narrative with filler content. It’s crucial to have meaningful subplots or thematic elements to avoid these pitfalls and maintain a well-paced narrative.

When crafting subplots, aim for depth and relevance, ensuring that each subplot serves a distinct purpose in advancing the overall narrative. Explore secondary storylines that intersect with the main plot but offer unique perspectives, character arcs, or thematic elements. Subplots can introduce new challenges, deepen character relationships, or delve into backstory elements, adding layers of complexity and intrigue to the story.

Tips And Tricks For Story Pacing

If you struggle with pacing well, there’s a good chance that you can already see yourself doing or not doing some of these issues. Hearing them and becoming conscious of which ones affect you most should help you improve some. However, there are more actionable things you can do to help improve your pacing too. With the issues out of the way, let’s get to the solutions.

Here’s how you can avoid the abovementioned issues and improve the pacing of your novels and screenplays. First things first, we’ll cover story structure for both screenplays and novels, touch on how to find and cut unneeded parts of the story, and finally, what it means to identify and stick to the pace of your story consistently.

Story Structures And Outlines

How you structure your story depends a bit on the medium. There are similarities regardless; All stories need a beginning, middle, and end, for example. However, there are some key differences as well. We’ll start with the screenplay structure and then move on to novels.

Basic Story Structure

There are numerous structures for outlining a story, the simplest being the three-act structure. Act One is where you introduce the characters and plot and begin setting the stage for the conflict unfolding. The first act should be about 25% of the overall story.

The second act is where the plot and conflicts start to build tension. The characters react to the incident from act one, face resistance, and begin pursuing their overall goal. Then comes a turning point where the journey takes a significant turn, often involving a revelation or major confrontation. This second act should be 50% of the total story.

Finally, there is the third act. In the final act, the tension should increase even more as the story moves toward the climax. Everything you’ve hopefully built up to until now is close to wrapping up, and the tension is often quite high as the protagonist nears the resolution of the plot. Finally, loose ends should be tied up. This final act, like the first, is about 25%.

This may seem very formulaic, but that’s the point: it ensures you have an exciting pace when done right. There’s a reason why most feature films follow these percentages within a few minutes, and you should, too. If you want more info on this, check out – Screenplay Structure: Tips to Engage Audiences for a deep dive.

Proper Use Of Chapters

The three-act structure works well for novels as well as screenplays. So, you can easily use it as a simple story structure for books as well. However, novels have the added benefit of chapters, which are paramount in proper pacing.

How To Define A Chapter?

Essentially, they are sections of a novel that you can use in a repeatable way to ensure consistent pacing in your book. They don’t need to be a set thing; In fact, what a chapter is will differ for every book. And they can be as long or as short as they need to be as long as you can answer, ” What is a chapter in my book? What is the purpose?”

Each chapter will have its own structure that will be consistent throughout. For example, If you have a slow-paced story, one chapter could set the stage for something, the next could be the thing, and the third would be the aftermath. Think of this as a three-act structure where a chapter serves an act.

On the other hand, a fast-paced novel may have an incident and some resolution that drives the main plot all within a single chapter. In this case, each chapter would have a mini act one, two, and three and can be thought of as its own short story.

Using Chapters To Affect Pacing

Once you define your chapter structure, you have a “resting heart rate,” which you can consciously increase or decrease as needed and truly master your pace. When you’re consistent with what a chapter is, you can shorten or stretch the chapters from the standard to change pace.

If you do this well, it also helps reveal info slowly and ensure that the main characters are making active choices throughout the story instead of just happening, keeping readers engaged.

LivingWriter Outlines

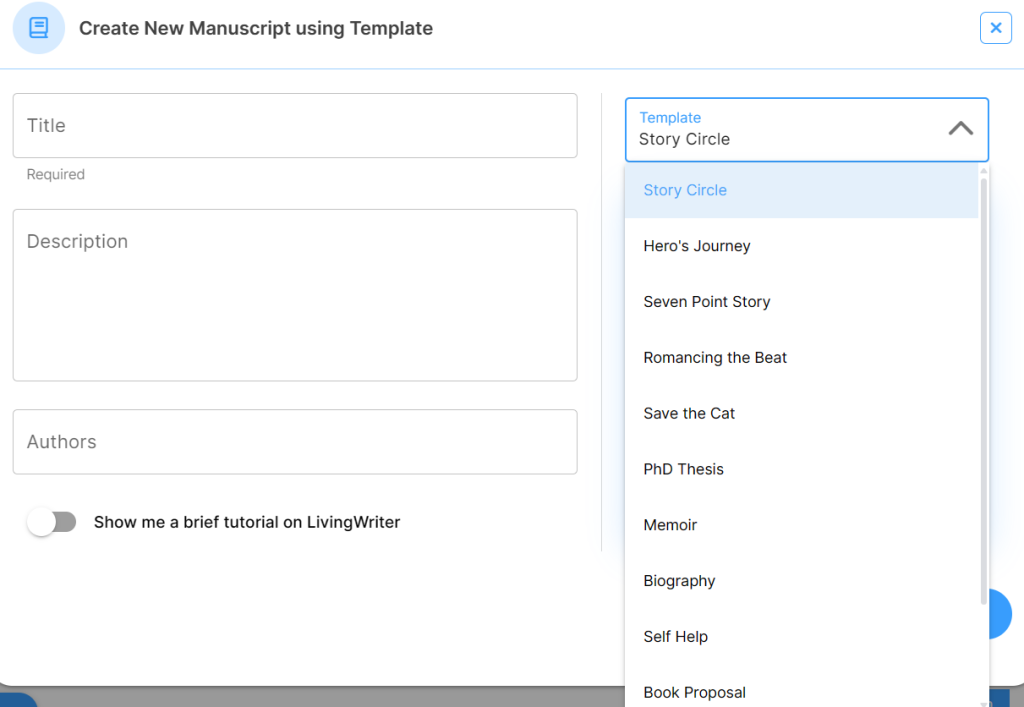

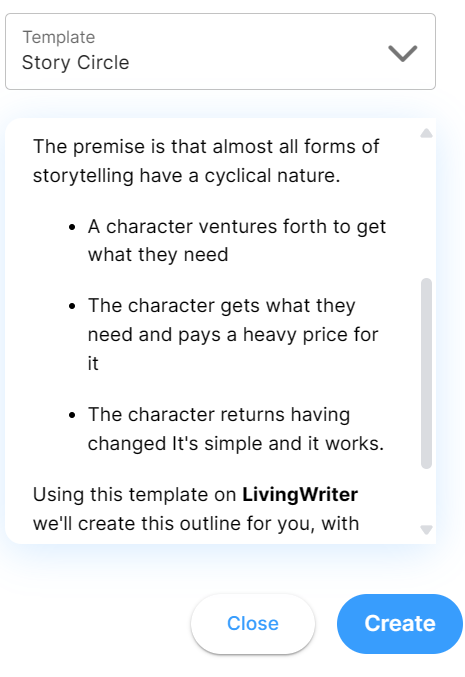

Writing with LivingWriter offers the convenience of several story structure frameworks built directly into the manuscript where you write. When you open a new manuscript, you can choose between several structures for different styles and genres.

There are general options, structures for specific genres (such as romance novels), screenplays, and even options for non-fiction authors and students. Once you’ve found one you’re interested in, clicking it will show you a small description.

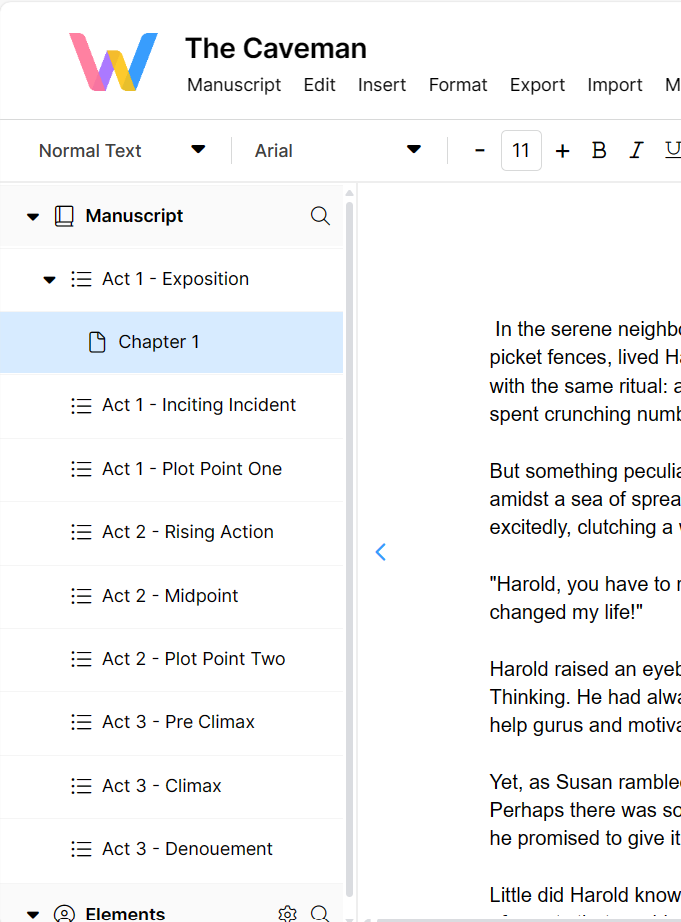

Once you’ve found the story structure that works for you and your story, you can provide a title and get the manuscript outline. From here, you can add chapters, scenes, sections, and notes for each template part.

This example shows Acts One, Two, and Three of the abovementioned three-act structure. Furthermore, each Act Is broken down further into three sections to help you along as you write. If you struggle with the pacing of your work, these built-in templates are highly effective at helping you improve.

You May Also Like: How LivingWriter’s AI Outlines Work

How To Write Engaging Sub-Plots

First things first, let’s look at what subplots are. On a basic level, they are secondary stories that get less time devoted to them than the main plot. Do they need them? Yes. As mentioned, a solid “A plot” alone isn’t enough for a fleshed-out story. However, you must strike a balance. Your sub-plot should not steal the show and overshadow the main plot.

At the same time, it must be important to the main plot and protagonist. If it isn’t, it won’t be meaningful or interesting to the reader and can distract from the main story. Some quick questions to determine a good subplot vs. an annoying sideshow are, “Does it affect the main character or plot? Why do they matter? And how does it impact the main character?”

Character, Role, Agenda, & Impact

It helps to think of a sub-plot in terms of a character. So, ideally, outline not a plot but a character—”I want this side-character to experience x,y, and z, which in some way influences the larger narrative.” This helps ensure your sub-plot is rooted in the characters and conflict of the main plot.

To do this, map out the character the subplot belongs to, their role in the story, their agenda, and how it impacts things. For example, let’s look at “The Dark Knight.” The main plot revolves around Batman’s efforts to stop the Joker’s reign of chaos in Gotham City.

Amidst this central conflict, a compelling subplot emerges involving Harvey Dent, the district attorney determined to rid Gotham of organized crime. Dent’s character, role, agenda, and impact are intricately woven into the narrative, as his pursuit of justice parallels Batman’s mission while also adding layers of moral ambiguity and complexity to the story.

Ultimately, Dent’s tragic transformation into the villain Two-Face is a dramatic climax that resolves his subplot and profoundly impacts the main plot and characters.

Conclusion

Mastering pacing is both an art and a science, requiring careful attention to the ebb and flow of your story. By implementing these techniques and experimenting with different pacing strategies, you’ll be well-equipped to create compelling narratives that captivate readers or viewers from start to finish.

Thanks for reading, and I hope you’ve found today’s article helpful. Until next time, happy writing.