How To Write Like Gillian Flynn

Gillian Flynn is probably best known for her novel (and subsequent film) Gone Girl. If you’re familiar with her bibliography, you’ll know that her other works, like Sharp Objects and Dark Places, are just as dark, gritty, and psychological. She pulls no punches, and as a result, her stories hit hard and stick with readers.

If you wish you had her style, you’re in the right place. Today, I’ll be teaching you how to write like Gillian Flynn. This means examining her writing style, which leans heavily toward complex characters, unreliable narrators, intricate plotting, and a deep dive into the darker aspects of human nature.

Below, we’ll cover what she does so well, how she does it, and how you can, too. Then, I’ll give you some practical writing exercises, further reading, and resources to help you put everything into practice. Sound good? Cool. Let’s jump right into how to write like Gillian Flynn in your work.

Table of Contents

How To Write Like Gillian Flynn

Before we can write like Gillian Flynn, we must understand what makes her work hers. As mentioned above, she is known for her complex characters, dark themes, and plot devices. So, let’s take a deeper look at some of these things.

1. Psychological Depth

First up, we must look at Flynn’s deeply psychological characters. What do I mean by deeply psychological? Well, her characters are usually significantly flawed, often wrestling with inner demons. Whether it’s a vengeful wife, a self-destructive journalist, or a traumatized child, her characters are complex, multidimensional, and far from perfect.

And Flynn is fully in their heads, aware of what makes them tick and why.

When creating your characters, dig deep into their psychology. Beyond their motivation for doing something, ask yourself what they fear, what drives them, and what secrets they keep hidden. These extra elements will make your characters feel real, relatable, and sometimes really twisted.

Here are some techniques and exercises to help you dig into the psychological layers of your characters.

Character Backstory Journaling

Create a journal entry from your character’s perspective. Write about a pivotal moment in their life that shaped who they are today. Focus on how this event affected their worldview, their fears, and their desires. This exercise will help you get inside your character’s head and understand what drives them on a deeper level.

For example, writing about the moment your character first experienced major betrayal roots their inability to trust others in something tangible and can give you a lot of influence over their relationships and behavior in your story.

Inner Conflict Mapping

Identify and map out your character’s inner conflicts. These conflicts often stem from their deep fears, insecurities, or contradictions. For example, a character might crave intimacy but also fear vulnerability. Tension like this can create a compelling internal struggle that adds depth to their actions and decisions.

To do this, I like to draw a diagram that highlights at least two conflicting desires or fears within a character. For each, note how it influences their behavior and relationships in your story.

The Secret Exercise

Everyone has secrets, and complex characters should, too—some known only to themselves. Write down three secrets that your character keeps hidden from others. Think about how these secrets shape, affect, and influence the character.

Imagine, for example, that a character secretly resents a sibling, even as they outwardly support them. This hidden resentment would probably lead to subtle, passive-aggressive behavior that complicates their relationship.

Secrets are also a great tool to gradually create tension and add layers to your narrative, since you can play with gradually revealing them.

Dialogue as a Window to the Psyche

Use dialogue to reveal your character’s psychological traits. Flynn often uses sharp, revealing dialogue to uncover what’s really going on inside her characters. Pay attention to subtext—what your character says versus what they truly mean. Dialogue can be a powerful tool to show rather than tell your character’s internal struggles.

You May Also Like: How To Write Dialogue In A Story

When you write certain scenes, play with your character saying one thing but meaning another. Pay close attention to how their words, tone, and even body language reveal deeper emotions or intentions that they don’t fully divulge.

2. Unreliable Narrators

Spoiler Alert: I discuss some plot points for Gone Girl below.

One of Flynn’s trademarks is the use of unreliable narrators, which keeps us questioning the information we get, adding layers of mystery and suspense to her stories. For example, In Gone Girl, Nick Dunne serves as an unreliable narrator due to his withholding of key information.

As the story unfolds, readers learn that Nick has been lying about his affair and his feelings toward his missing wife, Amy. His partial truths and omissions create doubt in the reader’s mind, making it difficult to discern whether he is guilty of her disappearance.

By withholding information and presenting a carefully constructed facade, Flynn masterfully creates a sense of ambiguity and suspense, forcing readers to question everything they know about the characters and the plot.

Writers need to practice subtlety and precision to effectively use unreliable narrators. Here is what I recommend for getting your less-than-trustworthy narrators to work well.

Start with the Character’s Perspective

First, immerse yourself in the character’s mind. As mentioned above, we should already understand their biases, fears, and motivations. So, now ask yourself: What does this character want the reader to believe? What are they trying to hide or justify? This internal conflict should naturally influence how they tell their story.

Learn more about different character POVs.

Selective Disclosure

An unreliable narrator often shares only selective details, whether intentionally or unintentionally. When writing, decide what your narrator knows but isn’t revealing. For example, they might skip over crucial facts or describe events in a way that reflects their personal bias.

Flynn’s Nick Dunne in Gone Girl omits his affair initially, and from his POV, it’s understandable why. This is yet another case of being conscious of and intentional with your character’s inner workings. When we, as writers, know the outcome they want and why, it becomes clear what they might do to get it.

Contradictions and Inconsistencies

Lying is hard in real life, and spinning a web of deceit is challenging to maintain. That said, when someone fabricates something, it’s rarely perfect. So, introduce subtle contradictions in your narrator’s account of events.

These could be small details that don’t add up or changes within their story that seem off over time. This will create a sense of unease in the reader and make them question how much of what they’re hearing they can believe.

Foreshadowing and a clear plan for your plot and character arcs are a big help. By strategically placing inconsistencies and unreliable information, you’re inviting your readers to become detectives. They’ll actively participate in piecing together the truth, creating a deeper connection to the story.

Test Your Narrator’s Reliability

Once you’ve written your unreliable narrator, re-read the story from a neutral perspective. Ask yourself if the inconsistencies and selective disclosures are subtle yet effective. If they’re too obvious, the reader may catch on too quickly; if they are too hidden, they might not realize the narrator is unreliable at all.

3. Plot Twists

Gillian Flynn is well known for her ability to lead readers down a particular narrative path, only to shift the story in an unexpected direction. This not only keeps readers on their toes but also heightens the suspense and emotional impact of the story.

That said, plot twists must be well set up and justified, or they can do more harm than good. A good plot twist will feel like a significant, often profound, shift in the reader’s perception of the philosophical conflict within the story—not a cheap 180 or misdirection just for the sake of surprise.

To do plot twists well, we have to understand there are three separate shift points, and you don’t want to leave any of them out. When you take the story direction and flip it, the change will affect some number of the following elements:

- External Shift: This shift rearranges plot elements (characters dying, discovering something unknown, etc.); these have nothing to do with character belief or the elements of the story.

- Internal Shift: Causes a change in the emotion of the story (characters going from hope to despair or vice versa)

- Philosophical Shift: Cause a change to the perception of the story themes (for example, a theme that was initially viewed as good starts appearing flawed)

The philosophical shift ultimately justifies the twist in most cases. If we stop and ask why we should use plot twists, the best answer is that they mimic life. Many times throughout life, people experience unexpected external events that change how they see the world from that point on.

The best plot twists often involve all three types of shifts—external, internal, and philosophical—to create a multi-layered experience that resonates deeply with the reader. By understanding and employing these shifts, writers can craft plot twists that not only surprise but also enrich the story, making it more reflective of the complexities of real life.

How To Do Plot Twists

1. Plan Your Twists Early: Before writing, outline your key twists and decide how they’ll affect your story.

2. Layer Your Twists: Combine different shifts for maximum impact. For example, an external event (like a betrayal in a seemingly perfect relationship) could lead to an internal emotional shift (such as becoming cynical) and a philosophical revelation (even the strongest relationships can fall apart).

3. Use Subtle Foreshadowing: Plant small, subtle clues early on to hint at the twist without revealing it. This builds cohesion and makes the twist feel earned. You want the reader to be surprised but able to see the breadcrumb trail in retrospect.

4. Ensure Believability: Make sure your twist aligns with your characters’ established traits and the story’s logic. Again, it should feel like a surprising yet natural outcome. Using the relationship example from number 2, any established insecurities and fears could make them vulnerable to exploitation, leading to a believable twist.

5. Reveal Gradually: Let the truth unfold in layers, keeping readers engaged and building suspense. Save the full reveal for a moment when it will have the most impact. And again, it should be something they didn’t see coming, but it should not feel like it came out of thin air as a “gotcha!” moment.

6. Get Feedback: Before finalizing your twists, seek feedback from others. Ask if the twist surprised them, felt natural, and deepened their understanding of the story.

4. Motifs And Dark Themes

Flynn’s work is not dark like a gnarly horror movie may be, but she tends to focus on the not-so-bright side of human nature in an authentic way. She commonly delves into the complexities of human nature, revealing the potential for darkness to exist within even the most seemingly ordinary individuals.

You May Also Like: Most Overused Horror Cliches – Top 10

Here are some tips on tapping into some of these darker motifs and themes without using shock value or gratuitous violence.

Focus on Human Relationships

At the core of Flynn’s work are complex, often toxic relationships—something most people have experienced, which can be very harmful both physically and mentally. Whether the marital deception in Gone Girl or the fraught sibling dynamics in Sharp Objects, these relationships drive the narrative and provide a rich source of conflict and tension.

When writing about relationships, dig deep into the power dynamics at play. What do the characters want from each other, and how do these desires clash? What hidden resentments, unspoken truths, or past betrayals influence their interactions?

The more layered and conflicted these relationships are, the more they engage the reader. Consider writing scenes that reveal different facets of these relationships, showing how they evolve (or devolve) over time. This approach will make your characters feel more natural and your plot more intricate.

Social Commentary

Flynn often weaves social commentary into her narratives, whether it’s a critique of gender roles, an exploration of media influence, or a look at class disparities. These themes add depth to her stories, making them resonate on a broader level.

To incorporate social commentary into your writing, I recommend thinking about how your story’s setting, characters, or plot elements might reflect larger societal issues. Explore how societal expectations shape your characters’ choices or how a particular social issue impacts the world of your story.

You May Also Like: How To Write A Novel: Simple 5-Step Guide

For example, if a character comes from a religious family in the South, divorce might not be a socially acceptable way out of her marriage. As a result, she may push her husband away or take more drastic measures. This is a great way to think about how setting and social dynamics play a role in plot realism.

This doesn’t mean your story needs to be overtly political or preachy—sometimes, subtle commentary can be more powerful. Consider what questions you can ask, any assumptions you can challenge, or new perspectives you can offer on familiar issues with your plot.

Moral Ambiguity

One thing I love about Flynn’s work and her use of complex relationships is how characters become somewhat morally ambiguous. This moral grey area can lead to an erosion of trust and love as characters struggle to understand and reconcile the conflicting aspects of their loved ones.

Dynamic relationships make it difficult to determine who is truly in the wrong. Both parties may have valid reasons for their actions, and the line between victim and perpetrator can become blurred. This is a beautiful thing in storytelling, as it challenges readers to question their own assumptions and biases.

If you can hone in on your characters and the aspects I’ve covered above (such as their psychology, fears, and motives), you can achieve this in your work; I believe in you. Just remember that things are usually not as black and white as we think, and people usually do things because they feel they are right or at least justified.

5. Complex Female Villians

Gillian’s novels are known for their “not your typical female character” leads who defy traditional stereotypes. Flynn deliberately avoids conventional female roles in her writing, rejecting the idea that women should be portrayed as inherently good or selfless, saying:

“For me, it’s also the ability to have women who are bad characters … the one thing that really frustrates me is this idea that women are innately good, innately nurturing. In literature, they can be dismissably bad – trampy, vampy, bitchy types – but there’s still a big pushback against the idea that women can be just pragmatically evil, bad and selfish…”

Gillian Flynn on Gone Girl and accusations of misogyny

Flynn laments the lack of potent female villains in literature and has made it a point to create them in her work. Her female antagonists are often driven by a mix of revenge, power, and survival, making them formidable, memorable, and sometimes downright villainous.

To explore this yourself, consider giving your story a female antagonist who is as compelling and multi-faceted as your protagonist. Explore her backstory, motivations, and how her actions drive the plot forward.

Avoiding Stereotypes

Don’t be afraid to subvert stereotypes in your writing. If you find yourself leaning towards a conventional portrayal, challenge it. Ensure she is more than just “evil for the sake of being evil”—give her a purpose that readers can understand, even if they don’t agree with it. Allow them to be flawed, to make mistakes, and to exhibit traits that might be considered “unlikable.”

We all know we can write female villains, but we should do it with the same gusto as Stephen King did with Annie Wilkes.

Practical Writing Exercises

It can be difficult to digest and apply all the steps above at once and cohesively integrate them into a single story. That said, you can practice all of Gillian Flynn’s stylistic elements independently with writing exercises. Some encourage you to write single scenes, while others work best with a short story.

They’ll all significantly improve your writing if you do them enough and familiarize you with what makes Flynn’s work hers.

- Character Flaws: Write a scene where a character’s flaw gets them into trouble. How do they handle the situation? What does this reveal about them?

- Unreliable Narrator: Write a short story from the perspective of a narrator hiding something from the reader. How can you drop subtle hints about the truth?

- Plot Twist Planning: Write a story with a twist that challenges the philosophy from what the reader would expect. Work backward to plant clues and misdirections.

- Female Characters:

- Write a short story featuring a female protagonist with a morally questionable goal. Explore her motivations and the lengths she will go to achieve her objective. Focus on how her actions reveal both her strengths and weaknesses.

- Develop a female antagonist for a story. Outline her backstory, motivations, and key scenes where she takes center stage. Focus on making her actions and decisions as justifiable in her mind as the protagonists are in theirs.

Further Reading And Resources

If you’re interested in writing like Gillian Flynn, I recommend these books, tools, and resources.

Books to Read

Of course, after reading this article, it would be helpful to read (or reread) Flynn’s novels. As you read, you’ll start to pick up the things I’ve mentioned and be able to better relate to what she’s doing and why. Here is a list of her books and their Amazon pages if you want to pick them up.

- Sharp Objects (2006)

- Dark Places (2009)

- Gone Girl (2012)

- The Grownup (short story) (2014)

It would help to read other psychological thrillers for further inspiration and different takes on the things I’ve covered. This is by no means a comprehensive list, but here are some that I recommend if you’re looking for novels with similar elements to Gillian Flynn’s work.

1. “The Girl on the Train” by Paula Hawkins

- Similarities: Like Flynn’s work, The Girl on the Train features an unreliable narrator, complex female characters, and a plot of twists and turns. The story revolves around a woman entangled in a missing person’s investigation after witnessing something suspicious during her train commute.

- Why It’s Good: The novel explores themes of obsession, memory, and the consequences of deception, much like Flynn’s exploration of dark psychological landscapes. Plus, the unreliable narrator, complex female characters, and plot twists.

2. “Before I Go to Sleep” by S.J. Watson

- Similarities: This novel features an unreliable narrator in Christine, who loses her memory every night when she falls asleep. As she tries to piece together her life and figure out who she can trust, the tension and suspense build in a way that fans of Flynn will appreciate.

- Why It’s Good: The novel plays with the themes of memory, identity, and the fear of the unknown, creating a sense of unease that mirrors Flynn’s novels. It again uses a less-than-perfect narrator and flawed female lead.

3. “The Silent Patient” by Alex Michaelides

- Similarities: The story revolves around a famous painter who suddenly stops speaking after being accused of murdering her husband and the psychotherapist determined to uncover her secret.

- Why It’s Good: The novel’s intense psychological focus and unexpected twists make it a great companion to Flynn’s work, especially for readers who enjoy dissecting complex character motivations.

4. “Big Little Lies” by Liane Moriarty

- Similarities: While more domestic in scope, Big Little Lies shares Flynn’s interest in exploring the darker undercurrents of seemingly normal relationships and lives. The novel weaves together the stories of three women, each dealing with their own secrets and lies, leading to a shocking climax.

- Why It’s Good: The novel’s intricate plot, strong female characters, and commentary on social issues make it a thought-provoking read with a similar tension to Flynn’s narratives.

Writing Tips

Here is a list of articles that will be useful in brushing up on your writing fundamentals and can help you execute the advice I’ve given above:

- 12 Common Beginner Writing Mistakes You Must Avoid

- Mastering Pacing In Novels And Screenplays

- Write Better Characters And Plots – 5 Tips

- Integrating the Styles of Famous Authors into Your Unique Voice

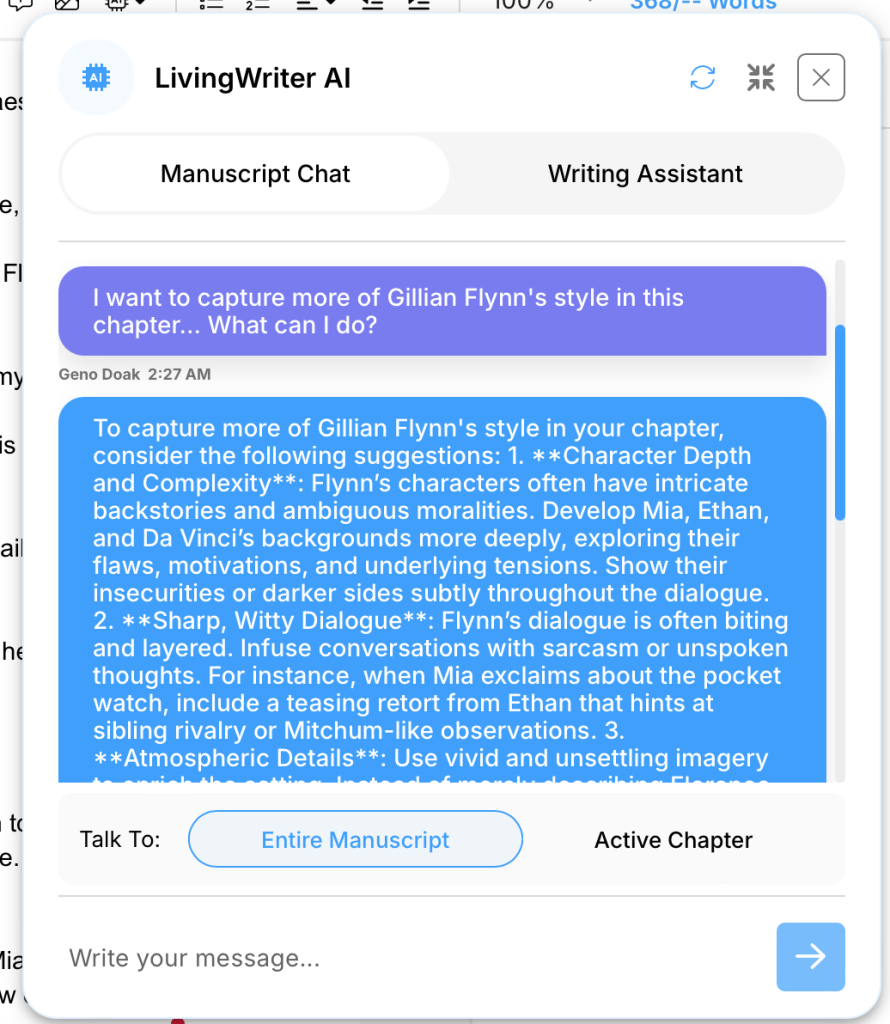

LivingWriter Tools

Writing on LivingWriter makes every aspect of your writing easier. With well-organized manuscripts, devoted research sections, and character integration, writing has never been more convenient. There are also helpful AI features like outline generation, AI rewrite, tone analysis, and more.

The Manuscript Chat features can be extremely valuable when trying to incorporate the voice or style of a particular author. For example, I asked quite simply: How can I make this section I’m working on more like Gillian Flynn’s work? And it gave me feedback and advice tailored to my story and characters:

It not only gives useful general advice but also specific suggestions for which part of my dialogue I could change and how to achieve the style I was going for. There is a reason LivingWriter was voted the best app for writing in 2024 and given number one in this article on The Best Writing Apps and Book Writing Software by Ameredian.com. It’s genuinely a writer’s best friend.

Conclusion

Writing like Gillian Flynn means embracing the darker sides of human nature, crafting intricate plots, and developing complex characters. If you’ve made it this far, you now have the tools to start practicing doing those things in your work. So, get out there and get to work. Until next time, happy writing, my friends.