Writing Compelling Screenplays – 6 Advanced Tips

Sometimes, as screenwriters, we have all the basics down and still don’t come away with anything genuinely captivating or engaging. Or the screenplay is well-written but doesn’t translate well to the screen. If you write, you’ve undoubtedly been here. But fear not! This article will dive deep into some advanced strategies for writing compelling screenplays beyond the basics you probably already know.

From nonlinear narratives to experimental techniques, we’ll explore innovative approaches that will help you elevate your storytelling game and create screenplays that leave a lasting impression. Beyond that, we’ll also cover strategies to craft screenplays that read well and translate effectively to the screen. So, without further ado, let’s learn how to write compelling screenplays.

How To Write Compelling Screenplays

Let’s assume that you know most of the general rules of storytelling. We need a plot—in other words, an idea with some conflict and resolution and a beginning, middle, and end. We need well-written characters (with clear motivations) that experience some growth or change throughout the narrative and resonate with viewers.

You May Also Like: How To Get Ideas For Writing – 6 Must-Know Tips

These are all pretty basic ideas for writing a screenplay. While these are undoubtedly important (and we will naturally touch on some of these ideas), today, we’re discussing ways to ensure that we have some x-factor or element that grabs the audience and takes them for a ride.

Writing Nonlinear Narratives

We’ve all heard that stories need a beginning, middle, & end, and they do. However, they don’t have to happen in chronological order, and that’s precisely what a nonlinear narrative does; It tells the story’s events out of order.

Nonlinear storytelling can add a lot of complexity and depth to your screenplays. Films like Pulp Fiction and Memento show how well the technique can keep audiences on the edge of their seats and challenge traditional storytelling conventions.

Why Nonlinear Plot Works Well

They do this through several means. First, they often create a lot of suspense. For example, if you leave one character or timeline on a cliffhanger and jump elsewhere, viewers will be left waiting to see the next portion or resolution.

Next, you can play around with who knows what. Let’s say characters 1 & 2 are plotting a setup on character 3. Jumping from the point of view of the schemers (who know the plan) to the victim (who doesn’t) can be a very entertaining way to approach the narrative, especially for film.

Nonlinear Narrative Tips

While a nonlinear story can be very helpful in crafting an engaging screenplay, it is undoubtedly more complex. As a result, you’ll want to consider and be cautious about some things.

First, you’ll have to plan the story out meticulously. When jumping around in the narrative, we must know where we’re at and where we want to go in terms of story. Without a map, it’s very easy to end up with a mess of incohesive scenes.

On a similar note, your transitions or shifts should be very clear. Your viewer (and you as the writer) should always have a clear idea of what timeframe, world, character, etc, the story is in and when they change. I include break lines in the actual manuscript to help with this while everything is still on paper.

Another thing is to maintain consistency with character development and story events across the timeline. Say something big happens while in the POV of a particular character, and then we jump to another. Is the new perspective from the same exact time? Is it their experience of the same event or sometime before or after? These are all things you’ll have to consider and keep up with.

How To Use Subtext

Subtext may be the single most important element of an exciting, compelling screenplay. So, what is subtext? In short, it’s the unsaid meaning behind a dialogue or action—the true meaning or intent behind what people say and do.

It’s been said that people say about 10% of what’s on their mind… Well, the subtext is that unspoken 90%. For example, if Jack says, “So, you’re finally taking the day off. Must be nice.” Jack’s comment shows clear resentment or jealousy towards the person taking the day off.

The subtext implies that he also wants to take time off or disapproves of the other person’s decision.

Next, consider the famous line from The Shawshank Redemption: “Get busy living, or get busy dying.” This line, spoken by the character Andy Dufresne, carries a deeper meaning beyond the words and suggests themes of hope, redemption, and the choice between embracing life or succumbing to despair.

Subtext will carry much of your work’s underlining symbolism, theme, and message.

Context Matters

You can think of subtext as text + context. Take a line like, “No. I’m not going back.” Now imagine it being said by a convict who has escaped prison but is being recaptured. That context gives the line a completely different, very heavy meaning than other circumstances.

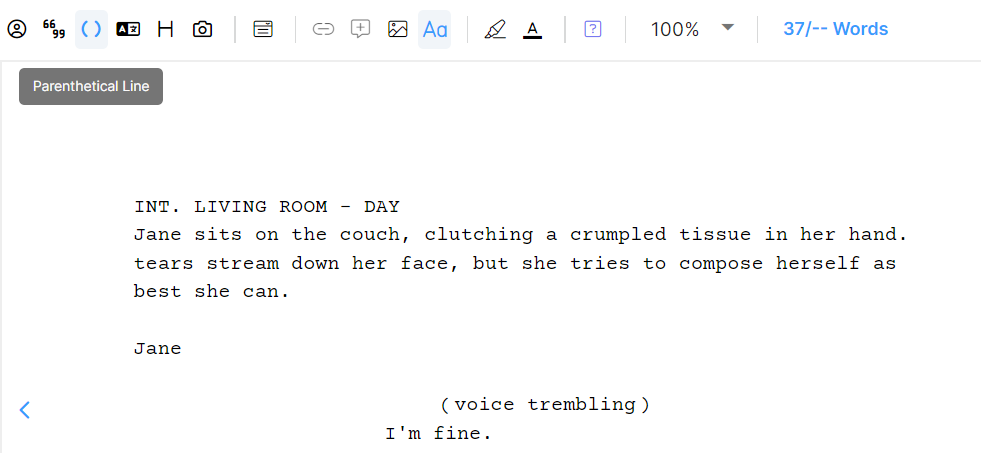

You can also use actions and contradictions to your advantage. Consider a line like “I’m fine” spoken by a visibly upset character on the verge of tears. In this context, the subtext suggests that the character is not fine, despite their words. In times like this, using scene description and parentheticals is essential to the scene.

Unspoken things like someone staring off into space as they talk or slamming a door as they leave can tell the audience much, even beyond the dialogue. This is why you hear the adages like “show, don’t tell,” and “actions speak louder than words.”

Our job as writers is to provide the actors with enough context to perform well. In this sense, less can be more. You want to give them enough clues about what should be happening to paint a clear picture of the things beneath a scene, character, or film. But allowing them freedom with the character’s body language and mannerisms.

Use Of Narrative Devices

Literary or narrative devices are elements that help make viewers perceive the story as you want.

We often hear people talk about them in relation to novels. While the execution and emphasis of these literary devices may vary between novels and screenplays, many principles remain consistent in both forms of storytelling. Each device offers screenwriters unique opportunities to enhance their scripts and engage their audience on multiple levels.

Here’s a quick list of some elements I recommend you explore if you want to add more depth to your screenplays.

Allusion

Allusions to real-world elements can add depth and context to a story in screenwriting, providing cultural references that resonate with the audience.

For example, in a crime thriller screenplay, a detective character investigating a series of murders makes a passing reference to “Sherlock Holmes” while discussing the modus operandi of the killer with their partner.

This allusion to the famous detective highlights the detective’s observation and reasoning skills. It also adds a layer of familiarity for the audience, instantly evoking the archetype of the brilliant investigator. This is a subtle tool that works well to help viewers effortlessly connect the dots between real life and the screen.

Diction

Choice of words, tone, and style are crucial in screenwriting to convey character voice, set atmosphere, and create an overall mood. While the dialogue is a primary vehicle for diction in screenplays, descriptions and action lines also contribute to the overall tone.

Diction can refer to very general things like how formal or informal your dialogue is and more subtle things.

If one character angrily accuses the other of being “selfish” and “heartless,” while the other character responds with defensive phrases like “I’m just looking out for myself” and “You don’t understand,” the choice of words conveys the escalating tension and underlying emotions between them.

One character’s sharp, accusatory tone contrasts with the other’s defensive and dismissive tone, creating a dynamic exchange that underscores the conflict between the characters. Intentional use of diction leaves viewers with a lot to discover and unpack.

Allegory

An allegory is a literary device in which characters, events, or settings represent abstract ideas, moral qualities, or historical events. It often involves a deeper or symbolic meaning beyond the literal interpretation. Screenplays can incorporate allegorical elements to convey deeper themes or social commentary.

We touched on subtext above, which also does this, but allegory tends to be interwoven with the entire narrative. A famous film with a clear allegory is The Matrix, where the story’s premise of humans living in a simulated reality serves as an allegory for societal control, individuality, and the quest for truth and freedom.

Juxtaposition

Juxtaposition is putting two opposing things side by side. Contrasting screenplay elements can create tension, highlight themes, or underscore character development, similar to its use in novels. Juxtaposition can be used in single lines of dialogue, scenes, characters, or the entire plot.

On the level of a single line, consider the opening sentence of A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” Contradictory? Yes. Highly descriptive? Also yes. In terms of character, you could have someone trying to reach peace through violent means.

An excellent example of an entire story with a strong juxtaposition is The Shawshank Redemption. Throughout the film, there is a stark contrast between the harsh realities of prison life and the hopeful, redemptive themes portrayed through the friendship between Andy and Red.

Emotional Depth In Screenplays

Emotional depth is essential for a compelling story. This can be built in a few ways. First, it is essential to define what your characters want and need and how they will get it. Once they do, how does that change them? Next, what are the overall defining emotional themes of the film? Here are some tips to answer these questions.

Character Want Vs. Need

A character’s want drives their motivations and actions on a conscious level and moves the story along. Their need is a more profound, underlying thing that the character needs to grow or live a truly happy life. Once again, let’s look to a classic film for an example of want vs. need and how it provides emotional depth to the story.

In Forrest Gump, Forrest has a clear want throughout the story—to reunite with his childhood friend and love interest, Jenny. Forrest’s love for Jenny drives many of his actions and decisions, leading him on a journey across decades and through various historical events.

However, Forrest’s underlying need is more complex and profound. Beyond his desire for romantic companionship, he needs to find purpose and meaning in his life. Throughout the film, Forrest grapples with feelings of inadequacy, self-doubt, and confusion about his place in the world. Despite his apparent simplicity, Forrest yearns for acceptance, belonging, and a sense of fulfillment that transcends his external achievements.

You May Also Like: How To Write Unique Characters With LivingWriter

The contrast between Forrest’s want (reuniting with Jenny) and his need (finding purpose and belonging) adds depth to his character arc and drives the entire emotional core of the story. While the pursuit of Jenny provides the narrative’s external framework, his inner journey of self-discovery and personal growth is what truly resonates with audiences.

Give Yourself Context

One of the best things you can do as a writer is understand your characters and what makes them tick. To do this, give yourself some context for their flaws, fears, and traumas. In other words, why do they act the way they do, and why do they have that underlying need we covered above?

In my experience, the best way to do this is to write scenes for these important events, even if they aren’t going in the script/movie, just for context and an idea of what may trigger the character. Let’s say we’re writing a screenplay about a detective investigating a murder case.

Our protagonist has a deep-seated fear of failure and a reluctance to trust others. To understand the origins of these traits, we could write a scene from the character’s past.

Backstory Scenes

Something like this:

After being assigned to his first major case involving a missing child, despite his best efforts, he fails to find the child in time, leading to devastating consequences.

The scene would show him experiencing and coping with this traumatic experience and paint a picture of why it instills in him a fear of failure and a belief that he must always be in control to prevent similar tragedies.

Although these backstory scenes may not appear in the final screenplay, they provide invaluable insight into your characters and inform their actions and decisions throughout the story. By delving into past traumas, we (the writers) gain a deeper understanding of what drives characters to want and can create more nuanced and relatable characters as a result.

Creating A Character Arc

How your plot changes your characters, and emotional resonance go hand-in-hand. As they move through the plot, they’ll change and grow as the narrative progresses—your Act One character should be in some way different in Act Three. This is what’s referred to as their “arc,” and it plays a significant role in connecting with viewers.

With the general story ideas in place, I suggest people consider this arc in reverse. Let’s use our flawed detective from above. His goal is to solve the murder case he’s investigating. His need is to overcome the fear of failure from a case he couldn’t solve in the past.

Where will he end up at the end? Let’s say he solves the current case (despite his traumas working against him) and can let go of the past. That’s our bullseye. If we stick a metaphorical arrow into that bullseye and then imagine a line from it back to the bow, we have an arc.

Ideally, you want the space between them to be so vast that a viewer cannot comprehend how our flawed Act One detective can reach that finish line. That’s the point: that opening character can’t do it. They must change, evolve, progress, heal, whatever it may be, to fulfill their need and get there.

When we do this successfully, this journey from start to finish, against all odds, invests readers in the story.

Ideas On Structural Innovation

Your screenplay needs structure, and there are several that you can use. Which one you choose depends on your preference and your screenplay. However, I want to mention Dan Harmond’s story circle specifically, as it can keep structure even amidst the most chaotic stories, scenes, and characters.

At its core, the story circle consists of eight distinct stages that guide the progression of a narrative, ensuring that critical elements are effectively conveyed. Here’s how you can use the story circle to enhance your writing:

| Establishing the Ordinary World | Begin by introducing the audience to the protagonist’s ordinary world, establishing their daily routine, relationships, and any underlying conflicts or desires. This stage sets the foundation for the narrative and allows viewers to connect with the character on a deeper level. |

| Triggering an Inciting Incident | Next, introduce an inciting incident or catalyst that disrupts the protagonist’s ordinary life and sets them on a new path. This event should propel the protagonist out of their comfort zone and spark the central conflict of the story. |

| Embarking on a Journey | As a result of the inciting incident, the protagonist embarks on a journey or quest to address the central conflict and achieve their goals. This stage is marked by uncertainty and challenges as the protagonist confronts obstacles and faces internal and external conflicts. |

| Encountering Trials and Tribulations | Along the journey, the protagonist encounters various trials and tribulations that test their resolve and force them to confront their fears, weaknesses, and insecurities. These challenges serve to deepen the character’s development and drive the narrative forward. |

| Reaching a Midpoint or Revelation | Following the climax, the protagonist experiences a resolution or transformation that brings closure to the central conflict and resolves any lingering questions or conflicts. This stage allows for catharsis and emotional fulfillment for the characters and the audience. |

| Facing the Climax or Ultimate Challenge | Following the climax, the protagonist experiences a resolution or transformation that brings closure to the central conflict and resolves any lingering questions or conflicts. This stage allows for catharsis and emotional fulfillment for both the characters and the audience. |

| Experiencing a Resolution or Transformation | Following the climax, the protagonist experiences a resolution or transformation that brings closure to the central conflict and resolves any lingering questions or conflicts. This stage allows for catharsis and emotional fulfillment for the characters and the audience. |

| Returning to the Ordinary World, Changed | Following the climax, the protagonist experiences a resolution or transformation that brings closure to the central conflict and resolves any lingering questions or disputes. This stage allows for catharsis and emotional fulfillment for the characters and the audience. |

The beauty of the story circle is that it applies to the concept of story in general and, therefore, can provide structure to anything. Bear with me as I break down a single scene from The Lord of the Rings as an example.

Scene: Frodo and Sam encounter the Black Rider at the Bucklebury Ferry

- Establishing the Ordinary World: The scene begins with Frodo and Sam traveling through the Shire, enjoying the peaceful countryside and their camaraderie. They are unaware of the imminent danger lurking nearby.

- Triggering an Inciting Incident: The incident occurs when Frodo spots a Black Rider approaching the road ahead. This sighting disrupts their ordinary journey and fills them with fear and uncertainty.

- Embarking on a Journey: Frodo and Sam realize they must flee the Black Rider and continue their quest to deliver the One Ring to Rivendell. They take the Bucklebury Ferry across the river to evade their pursuer.

- Encountering Trials and Tribulations: The Black Rider catches up as they approach the ferry, instilling a sense of urgency and danger. Frodo and Sam must navigate the chaotic scene and overcome their fear to reach safety.

- Reaching a Midpoint or Revelation: The midpoint occurs when Frodo realizes that the Black Rider is drawn to the power of the One Ring and must bear the burden of its protection alone. This revelation reshapes Frodo’s understanding of his role in the quest and deepens the stakes of their journey.

- Facing the Climax or Ultimate Challenge: The climax occurs when Frodo bravely confronts the Black Rider, using the power of the Ring to command the ferry to leave the shore. This confrontation represents the ultimate challenge for Frodo, as he must assert his will against a powerful enemy.

- Experiencing a Resolution or Transformation: Following the climax, Frodo and Sam escape the Black Rider and continue their journey towards Rivendell. This experience solidifies their bond and reinforces Frodo’s commitment to the quest despite the dangers ahead.

- Returning to the Ordinary World, Changed: As they depart from the ferry, Frodo and Sam reflect on the events that transpired and the challenges that lie ahead. They have been forever changed by their encounter with the Black Rider, and their journey will never be the same.

I make this lengthy example to show how the structure can be applied even on smaller scales. If you’re writing a chaotic, non-linear story or find yourself stuck on a scene or character arc, you can always revert to this sequence, identify which section is missing, and move forward from there.

The Art Of Visual Storytelling

Not all stories (even good ones) can play out in around 90 minutes and belong on the big screen. Some stories make better novels than movies, while others work best as TV shows. While there are no hard and fast rules for what makes a story movie-worthy, I encourage writers to ask the question, “Would this be a good movie?”

For film, we need something captivating enough to hold a viewer’s attention for nearly two hours. Yet, we must be able to tell the story entirely within this timeframe, which is relatively short compared to a book or TV series. Not all stories will fit the bill, and that’s ok.

If we can see a movie within our story, we must then pull it out. So, how do we do that? Regardless of the scale (long or short), your screenplay is a snapshot of events in someone’s (or many someone’s) lives. We must ask ourselves if this section of events, this snapshot, is the most important thing that’s ever happened to the character(s).

We want the answer to this question to be yes. One phenomenal technique I use to answer this is to stress test the idea with a trailer. Sit down and write a synopsis of the entire story that takes 2-3 minutes to get through. Introduce your character, some notion of what’s going to happen to them, what they’re going to do about it, why that doesn’t work, etc, all the way to the conclusion.

Is that three-minute story exciting and engaging? If so, you’re probably in the clear. If not, you either need to work on the plot more or consider that it may be better used in another medium besides feature film.

This vital engagement becomes apparent when you consider that script readers, directors, agents, etc, often only read the first page or so of the manuscript. If something doesn’t engage them right from the start, they likely won’t continue reading.

Concepts For Experimental Techniques

Now that we’ve established all these guidelines and concepts for writing a compelling screenplay let’s talk about breaking them. Can you break each “rule” I’ve given you so far? Absolutely. Should you? It depends. I would suggest you don’t deviate too far without a reason. Doing things for the sake of doing them is rarely a good idea.

However, if you have an idea that contradicts the “best practices” advice, you don’t have to abandon it. Instead, ask yourself how it can be helpful in a good, compelling story to break that principle. Perhaps the theme of your story is that sometimes you don’t get redemption. In that case, perhaps your protagonist, despite all their efforts, doesn’t make the change or let go of the past.

A lack of evolution in a screenplay with a different concept probably wouldn’t be a good thing. However, in the context of a “not all wounds can be healed” theme, this could be very emotional and gripping. So, in short, yes, you can break the rules if you have a good reason to do so.