How To Write Like Stephen King (And Still Be Unique)

Stephen King is often regarded as the “King of Horror,” and he’s got a style that has captivated readers for decades. With classics like The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile, his work is iconic even outside of horror. So, regardless of what genre you write, you can apply some of King’s methods to your process and work. Today, I’ll talk about how to write like Stephen King without copying him.

In addition to the ideas and tips you’ll find here, I’ll include examples and quotes from Stephen King himself wherever I can to give the most precise idea of what King does so well and why it works. Then, we’ll discuss a few writing practice exercises you can do to master the methods yourself. So, without further ado, let’s learn how to write like Stephen King.

How To Write Like Stephen King – 5 Key Techniques

Stephen King has written (somewhat at length) on why and how he writes in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. So, luckily, we’ve had a great deal of info from the man himself. If you’ve not read On Writing, I highly suggest you do so. It is a fabulous book and a great place to start if you want to know how King writes.

Beyond On Writing, we’ll delve into some particular things that he does that define his style and make his work recognizable and familiar to fans. You can incorporate these concepts and preferences into your work to significant effect without ripping off his characters and plot.

Flawed Characters

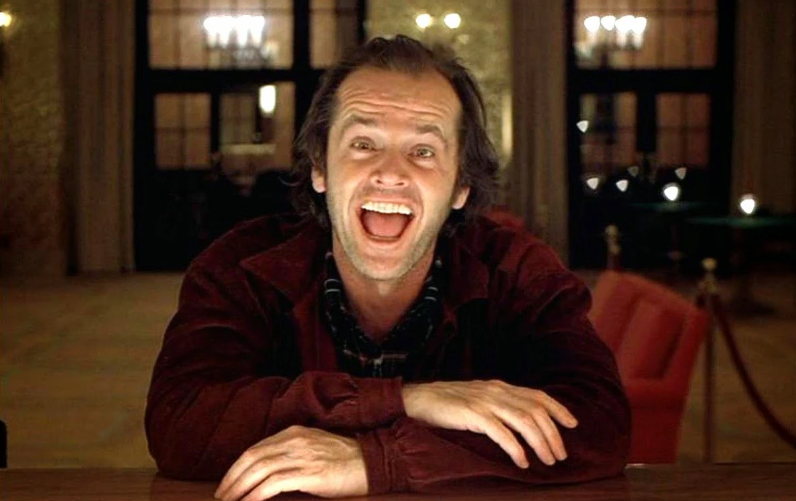

You’ve likely heard the advice that your “good guys” should have some flaws to make them less one-dimensional, more believable, and relatable – King takes things to a whole new level in this department, sometimes making his protagonists downright unlikable.

Jack Torrance from The Shining is a prime example of this. He’s an alcoholic, abusive to his wife, and prone to violence and all before he starts to go mad. By most accounts, he would not be a likable man, and he’s not a particularly likable character.

Another great example is Annie Wilkes from Misery – a disturbed and obsessive fan who holds her favorite author captive and tortures him. Annie’s extreme behavior and psychological instability are not your typical “relatable character flaw,” which makes her a chilling and unforgettable antagonist.

These are two of the most extreme examples I could think of to illustrate how far King is willing to go in making his characters flawed. Still, it’s a very common theme (to some degree or another) in much of his writing. It’s also worth mentioning that they’re not given these things for no reason.

The flaws of the characters play essential roles in the story. You couldn’t have the conflict in Misery without a character like Annie. So, if you want gripping characters that drive your plot, consider giving them some emotional or personality issues that extend far beyond the run-of-the-mill “ruthless ambition” or “trust issues.”

Active Writing

This is a more technical tip that King uses. He writes very actively. This means he often describes characters and settings through what’s happening or the characters’ actions instead of simply describing them. This is not to say heavily descriptive passages are bad, but Stephen King certainly describes them through action. Let me give you an example from Chapter 4 of IT:

“Eddie stood below, oblivious to the manholes opening and shutting in the street, oblivious to the laughter of children in the distance, oblivious to the first drops of rain that fell from the sky. He was in his yard, staring at the hat and seeing nothing but it, imagining it moving down the street of its own accord, like something from a horror movie.”

It Chapter 4,”Eddie Kaspbrak”

King paints a clear picture here – Eddie is in his yard. Manholes are opening and closing, children are laughing, it’s starting to rain, etc. But he shows Eddie’s thoughts and surroundings through his actions and observations instead of simply describing them.

For comparison, here is a hypothetical version of the same passage written in a less active voice:

“Eddie stood in his yard, staring at the hat. He didn’t notice the manholes opening and shutting in the street, the laughter of children in the distance, or the first drops of rain falling from the sky. His mind was focused solely on the hat, imagining it moving down the street on its own, like something from a horror movie.”

The scene is still set; all the info is there, but the less active version lacks the immediacy and engagement of the active writing style. Again, it’s not wrong to use more flowery descriptions in your work if that’s your style, but if you want those Stephen King vibes, try a more active approach when possible.

The Manuscript Chat Features on LivingWriter can help you identify how active (or passive) your descriptions are and provide feedback on moving them in the direction you want.

Third Person, Past Tense

In most of King’s books, he writes in the third person perspective and past tense. A quick example would be “He (3rd person) walked (past tense) along the dusty road, his eyes scanning the horizon for any sign of movement.”

It’s not wrong to write in the first person (King himself does in some short stories), but most of the time, he doesn’t. The third person past tense approach has a much more “being told a story” feel than the “sitting down and reading someone’s diary” feeling you get with other perspectives.

You’ve also got the distinct advantage of telling the reader things the characters don’t know when writing from a third-person perspective. Again, there’s no right or wrong answer here, but King heavily prefers the third person and the past tense, especially in his longer work.

Setting Size

King tends to scale his settings to the length of the book. This means his longer books have much larger settings (think The Stand), while his shorter stories (such as Cujo) happen in quite small, often confined settings. Some of this is for obvious reasons – Longer books have more time and space for more extensive settings.

What’s interesting is King’s seemingly intentional use of smaller, more claustrophobic settings for shorter stories. The Mist, for example, takes place within a small supermarket besieged by an otherworldly mist, trapping the characters inside and heightening their fear and desperation.

The use of smaller, enclosed settings contributes to an atmosphere of claustrophobia and amplifies the impact of the horror elements Stephen King often uses. If you’re writing shorter fiction and looking for that intense, uncomfortable feeling King does so well, consider keeping your setting small and prison-like.

Start With A “What If” Question

King often gets his story ideas from a simple “what-if” question that serves as the seed for the entire plot. For example, “What if a bestselling author was held captive by an obsessed fan?” (Misery) or “What if a farmer conspired to murder his wife?” (1922).

He also generally creates compelling characters to drive the plot forward, not vice versa. In On Writing, he says, “I want to put a group of characters (perhaps a pair; perhaps even just one) in some sort of predicament and then watch them try to work themselves free.”

This initial “what if” question is an excellent tool because it gives you that predicament up front and sets the stage for you as the writer to build your character-driven plot, as Stephen King does so well.

Writing Practice Prompts

Here are a few general “what if” questions that you can use to practice the ideas covered above. The stories don’t have to be particulary long, just experiment with “putting your characters into predicaments” and writing naturally to see where the story goes. These are Horror-themed prompts, but you can create your own for any genre:

- What if a hidden chamber beneath a town’s oldest building held unsettling secrets?

- What if you could see other people’s biggest fears?

- What if you found out someone was pretending to be you?

- What if mysterious disappearances in a suburban neighborhood were linked to an urban legend?

- What if a new home harbored unexplained phenomena from the previous owners?

- What if a lost hiker stumbled upon a reclusive community with dark intentions in a remote forest?

Conclusion

Hopefully, today’s article has given you some ideas as to how Stephen King manages to accomplish some of the things that make his stories so loved – The realism of his characters, the grit and imagination to his narratives, the active approach to descriptions that leave readers feeling like they’re on a runaway train, and how even his shorter works inspire a sense of dread.

Aside from understanding these concepts, you have an actionable plan (with guided practice) to integrate them into your writing. And considering these are general ideas, you can be confident that your stories emulate these positive aspects of King’s work without ripping him off.